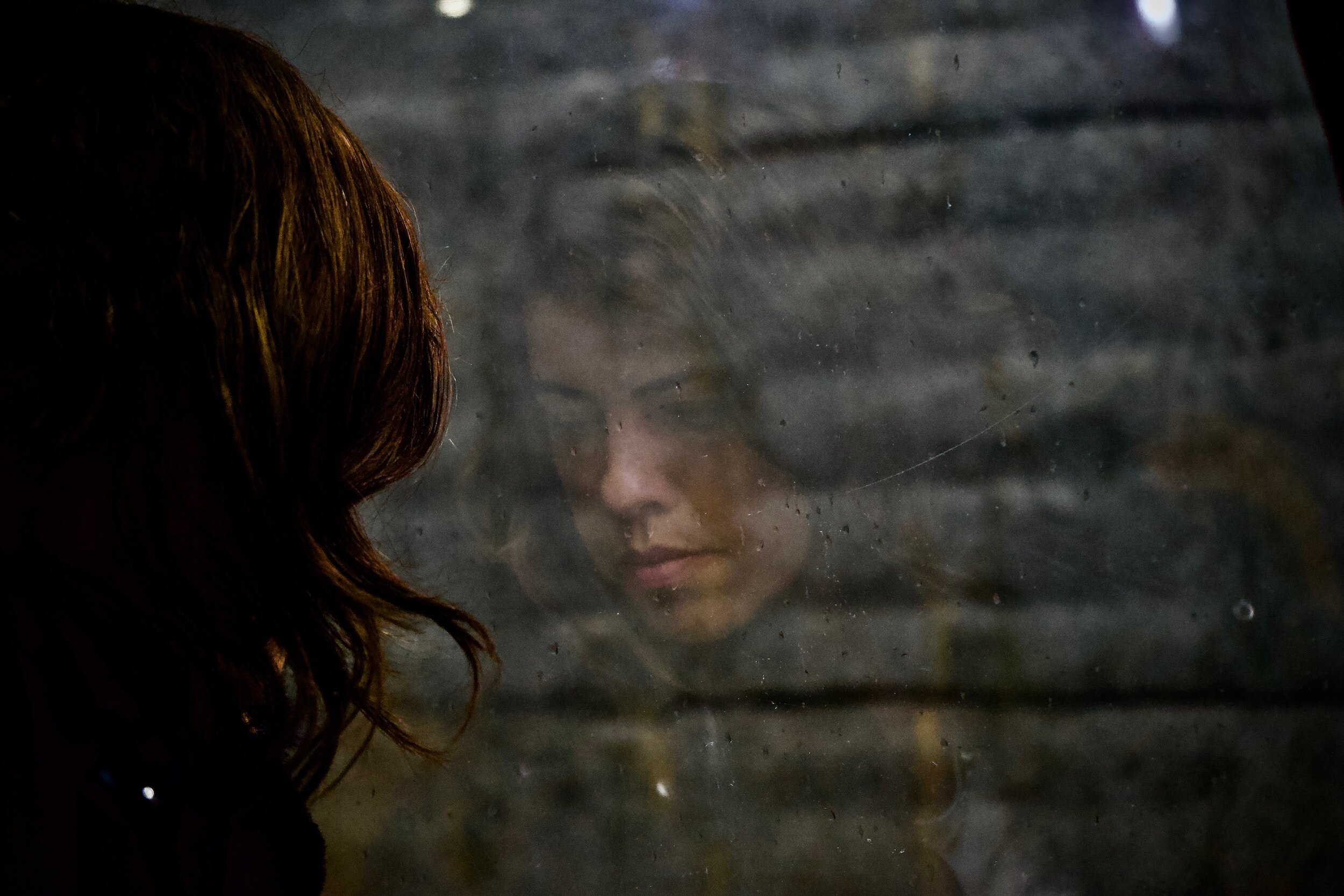

Attachment Wounds Leave Deep Scars.

We are hard-wired for connection. Yet, so many of us have core wounds of not-belonging and beliefs about our worthiness that were formed in environments devastated by generational trauma, fear, exile, and alienation. Healing is not easy, but it is possible.

Human beings are designed for togetherness. We are born to be completely dependent on our caregivers, and unable to survive without the protection, nourishment, and love of another human.

When children experience neglect, abandonment, or a primary caregiver who is chronically unavailable or dysregulated, this form of exile creates a core wound to our sense of belonging in the world. The lack of secure attachment in a child’s early years has been linked to a large number of mental illnesses, unhealthy coping strategies, and addictive behaviors.

When we experience abandonment or exile in these formative years, we make decisions about how the world works, based on the information we have available at the time. We may decide no one can be trusted, everyone leaves us if we need too much, all men are violent, or it’s not safe to be close because inevitably the people you are close to will hurt you. Or maybe we learn that we have to work really hard to earn love, that survival means staying on guard permanently, or that in order to keep our family safe we cannot ask for help, and that resting or relying on others means putting ourselves in danger.

Any psychology textbook that covers human development will summarize the work of Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby in the 1960s and 70s that shaped modern psychotherapy. These researchers theorized that based on our early experiences with our caregivers, we develop “schemas” or beliefs about ourselves as worthy or unworthy of care and attention, and others as reliable or unreliable sources of support.

Secure attachment occurs when we experience reliable attention and support, and our needs are met.

Insecure attachment occurs when there is a disruption in the process of bonding between the child and their primary caregiver. This is a type of trauma, and may take the form of abuse or neglect, or it may be more subtle, such as lack of affection or response from a caregiver.

Trans-generational trauma occurs when wounds are passed down through our genes and behaviors, from generation to generation, because there has not been resolution or healing. Epigenetic research on trans-generational transmission of traumatized behaviors in mammals even shows that exposure to stress hormones in-utero permanently impacts the behavior of offspring, even when those offspring are never exposed to the traumatized parent.

Healing attachment wounds begins with acknowledging our grief, and repairing our relationship to ourselves.

Researchers recognize four attachment styles which inform our behavior on a cognitive level that operates outside of conscious awareness.

Data suggests that approximately 50% of adults are securely attached, 20% are anxious (ambivalent), 25% are avoidant (dismissive), and the remaining 5% are fearful (disorganized) in their attachment style.

These are not meant to be defined as fixed states, and you may not fall cleanly into one style or another, but all of us exist somewhere on the continuum.

Secure: Your primary caregiver was likely a stable and predictable source of love and acceptance. They responded to your changing needs and were able to communicate safety non-verbally, and manage and express their emotions. In adult life, people with a secure attachment style:

Are comfortable with intimacy

Are resilient, can bounce back quickly from adversity

Are able to set appropriate boundaries

Feel safe, stable, and satisfied in close relationships

Can balance dependence and independence

Anxious (Ambivalent): Your primary caregiver was likely inconsistent. At times they may have been unavailable and distracted, or they may have been engaged and responsive. You may have been uncertain whether your needs would be met. In adult life, people with an anxious attachment style:

Crave closeness but struggle to trust or rely on your partner

Can be overly dependent, may feel threatened by too much space

Have a chronic fear of rejection

May need constant reassurance from their partner, may achieve this through manipulation, being needy

Define their self-worth by how they are being treated in relationship.

Avoidant (Dismissive): Your parent was likely unavailable or rejected you during your infancy. You learned to self-soothe because your needs were not adequately met. A deep fear of abandonment leads you to avoid relationships and reject intimacy later in life, as a way of protecting yourself from getting hurt. In adult life, people with and avoidant attachment style:

May end relationships to regain a sense of freedom

Are highly self-sufficient, and may withdraw when someone tries to get close

Feel they do not need relationships and that they do better on their own

Seek out independent partners who keep their distance emotionally

Fearful (Disorganized): Your primary caregiver may have been an unpredictable source of fear and comfort, and may have been dealing with their own unresolved trauma. Or, your parent may have ignored or overlooked your needs, creating confusion and disorientation in how you feel about relationships. In adult life, people with a disorganized attachment style:

May be controlling or untrusting of their partner

May abuse alcohol or drugs, and be prone to violence

Desire intimacy and find it confusing and scary.

Swing between feelings of love and hate

Could feel unworthy of love and be terrified of getting hurt